Across the Universe

2023 - 2024

Australian Prostate Centre / Exercise Physiology Class

Naarm / Melbourne, VIC

A Prostate Cancer Story

This Story is Dedicated to Leonard McCombe

“This is the way it usually happens.

You come in cold to an unfamiliar situation, where nobody knows you. The scenes you had imagined often turn out to be non-existent.

”What’s going on?” you ask yourself. “Where’s my story?”

It’s like being on the outside of a shop window looking in.

Somehow, you have to break through the glass.”

C61

Malignant neoplasm of prostate

ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases (Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification)

World Health Organisation

AcroSS the Universe

DYING from OR dYING wITH

Living with

Prostate Cancer

“Pools of sorrow, waves of joy

Are drifting through my opened mind

Possessing and caressing me”

PROSTATE CANCER has an increasing mortality rate in Australia; 3,900 men are projected to die from it in 2024, up from 2,700 in 2000. Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer, the 2nd deadliest cancer for men and the 4th for the entire population. It is the 8th leading cause of death overall.

Still, most men diagnosed with prostate cancer will survive. Stages I to III have an almost 100% survival rate 5 years from diagnosis. This sharply declines to 36% for Stage IV. By increasing awareness and reducing stigma, prostate cancer health care services aim to encourage more testing earlier, to shift more overall diagnoses back to the earlier stages where chances of chances of survival are highest.

Survival. It is the fundamental throughline of a life with prostate cancer.

But what does survival mean? How do you survive not dying from prostate cancer?

Particularly for men with aggressive prostate cancer that is either metastatic or likely to become so. Men who will undergo and endure treatments starting with radical prostatectomies and potentially followed up with radiotherapy, hormone therapy and chemotherapy.

These treatments can increase the chances of survival, although they bring with them side effects that can be physically and psychologically devastating.

A radical prostatectomy can shorten the penis by inches and result in “dry orgasms”. It can also, cause nerve damage, which in turn causes temporary or permanent erectile dysfunction. Bowel and urinary incontinence are likely as well.

Hormone therapy can shrink the penis and testicles, stop sperm production, cause impotence and end sexual desire. Some men refer to it as “chemical castration”. There is also the possibility of weight gain and bone density loss.

Tiredness and weakness are associated with radiotherapy, as are bowel and urinary difficulties and erectile function.

The collective consequences of the treatments strike painfully and deeply into the foundations of masculine identity. So deeply that some men will question to what extent they are still men.

The vigour and strength they once had, even just weeks before treatment, is lost.

Plans for family, career, home, retirement, travel and family, become indelibly bound to their illness, and some may be rendered unattainable. A few will decide to anchor themselves to capital cities because that is where the more, if not better, care is much more accessible.

There is a good chance they will feel isolated, societally and interpersonally. They will not find many people willing or able to listen to them talk about or understand the abject array of impacts they experience, many of which verge on taboo and are deeply personal.

Even partners may not have the capacity to hear them or, if they do, to know how to provide the right support. Partners are not aloof bystanders either. The impacts to men with prostate cancer are not confined to their own bodies; they can infiltrate and undermine relationships with the people they love. The physical intimacy they enjoyed with their partners can end because of sexual dysfunction. In the aftermath, some relationships will end.

Finding other men to talk about prostate cancer can also be challenging. Men with it would not be surprised if other men didn’t want to hear about it. It’s not that men don’t talk. It’s more likely to be a kind of defensive mechanism; not hearing about it means not thinking about it, which means avoiding the fear of thinking about the consequences.

More broadly, there is a feeling that society has little interest in their “old man’s illness”. Not only is that increasingly incorrect as a categorisation, as progressively younger men get prostate cancer, it also a trivialisation that diminishes and undermines them.

In the simplest sense, by the nature of their illness, these men are not now who they once were.

The transition can start with a shock from which they never fully recover and can engender a grief for what they have lost of themselves that never seems to completely dissipate. They stand in the present and look back across the gulf of time and space to the past vitality and joy of their youth.

All the while, their future is haunted by the spectre of mortality. They day to day, test to test and treatment to treatment, waiting for bad news and ignoring the good because it only records where they are at and not where they may yet still be. They look towards the statistical survival barrier that is “5 years from diagnosis” or “10 years from diagnosis”. If they push through it, what does that mean?

The old adage is true; more men will die with prostate cancer than from it. And many will say this as they talk about their prostate cancer. It is a kind of hopeful proposition, especially at the start of journey. But it also services to frame the beginning of the survivorship journey in the morbid context of where it ends - death.

Through exercise physiology classes for prostate cancer at the Australian Prostate Centre in North Melbourne, one group of men is working to reframe the context.

Instead of dying with or from prostate cancer, they are trying to live their lives with the highest quality they can, while they still have life to live.

Nothing's gonna change my world

“Limitless undying love

Which shines around me

Like a million suns

It calls me on and on

Across the universe”

“The most challenging aspects of living with prostate cancer are keeping on going and maintaining enthusiasm.”

“I’ll talk to my friends and colleagues and most of them don’t want to know about prostate cancer or prostate issues or incontinence issues. I think they’re scared. I think it’s fear. They don’t want to know if they’ve got it. They don’t want to know.

When I was talking to a friend about my experiences, he put his fingers in his ears.”

“With so many worthy causes for children and women, old men issues don’t seem as important.”

“It would be great to see more prostate cancer awareness in the Australian sporting scene, especially considering so many top sports are male dominated.

Similar to the pink games already happening for cricket and basketball - why not have a blue round each year to start the conversation around family history and normalise PSA testing?”

“It’s very scary because they initially gave me five years to live. Every day you wake up and you think you’ve only got five years to live, and you use up a year of it, and then you use up another year of it and you think, “How close am I to this thing exploding and taking over and taking my life?””

“The group has been my salvation.”

Coffee – 7am

On a dark, cold Friday morning, members of the Friday Group make their way to North Melbourne.

Some of them meet at St Cooper café for a coffee and catchup. Bleary eyed, they talk about anything and everything, from news, sports, arts and weather to recent holidays, how each other is doing, upcoming group social events and prostate cancer.

The café’s lights are as warm as the company; both help ease them into the morning before their 8am exercise physiology class for men with prostate cancer, run by the nearby Australian Prostate Centre.

John Hall waits for the 630am tram that will take him to North Melbourne, where he’ll meet other members of the Friday Group at St Cooper café. John was diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer (Gleason Score 9) in July 2022. It had spread to surrounding tissue and required a radical prostatectomy to remove the orange-sized prostate, seminal vesicles and nearby lymph nodes. 40 sessions of radiotherapy and hormone therapy (ADT) followed.

“I was diagnosed with an aggressive form of prostate cancer. Putting the adjective “aggressive” in front of “cancer” changes your outlook and it’s frightening. It had a Gleason Score of 9, which is Grade 5, the highest it can go.

I was shocked.

I was in a state of shock.”

John orders a coffee from Tabita Cooper, co-owner of St Cooper café (with partner Stephen Cooper). Of the several cafés in the area, the Friday Group gravitates to St Cooper because it gives them a comfortable place to sit and feel safe to talk. The now regular group often chats with Tabita and Stephen when they aren’t busy.

“We always had in mind having this cafe as more of a comfortable place for people to be having coffee, having a chat. And to know that this group is comfortable to come here to support each other, to talk about what they’re going through and being in is really great and we’re really happy that we have this base where they can do that.”

Michael Griffin (right) and John are usually the first of the Friday Group to arrive at the café. Because Michael’s parents lived in Belfast and he also spent several years there there with his own family, he is sometimes called “Irish Michael”. He was diagnosed in March 2019 (aged 53) with Stage IV metastatic prostate cancer, which has a 36.4% survival rate in the first 5 years after diagnosis. His treatments included radical prostatectomy, hormone therapy (ADT), chemotherapy and multiple courses of radiotherapy. His plans to become a chief financial officer before retiring to New Zealand ended with his diagnosis.

“The doctor said to me at the time that I was due for my PSA test [in 2019]. 2019 came and everything was going great. I was feeling awesome with no issues whatsoever. I had no inkling anything was wrong. Then [after the PSA test], it felt like a kick in the guts when my GP said we needed to investigate further.”

@ St Cooper Café

Ray Barber (right) is another Friday Group regular. Ray, 71, was diagnosed with prostate cancer on January 2020 and had a radical prostatectomy in April that year; the treatment was delayed by a bad cold and the COVID pandemic. Ray then had radiotherapy for 5 days a week over 7 weeks. Because his PSA was still rising after surgery and radiotherapy, he commenced hormone therapy (ADT).

Exercise Physiology Class – Warm up

In dribs and drabs, the Friday Group members arrive at the Australian Prostate Centre for their 8am exercise physiology class. As the coffee drinkers wander in, the others who go to the gym directly are as often as not already warming up.

The Australian Prostate Centre occupies much of the top floor of an 8-storey building with a dedicated gym that packs a lot of equipment into a small, repurposed office. Stationary bikes, treadmills and rowing machines sit alongside weight machines, free weights and an assortment of other types of equipment like medicine balls, resistance bands and aqua bags.

Molly Lowther, the Friday Group’s regular exercise physiologist, warmly greets the men before the class starts.

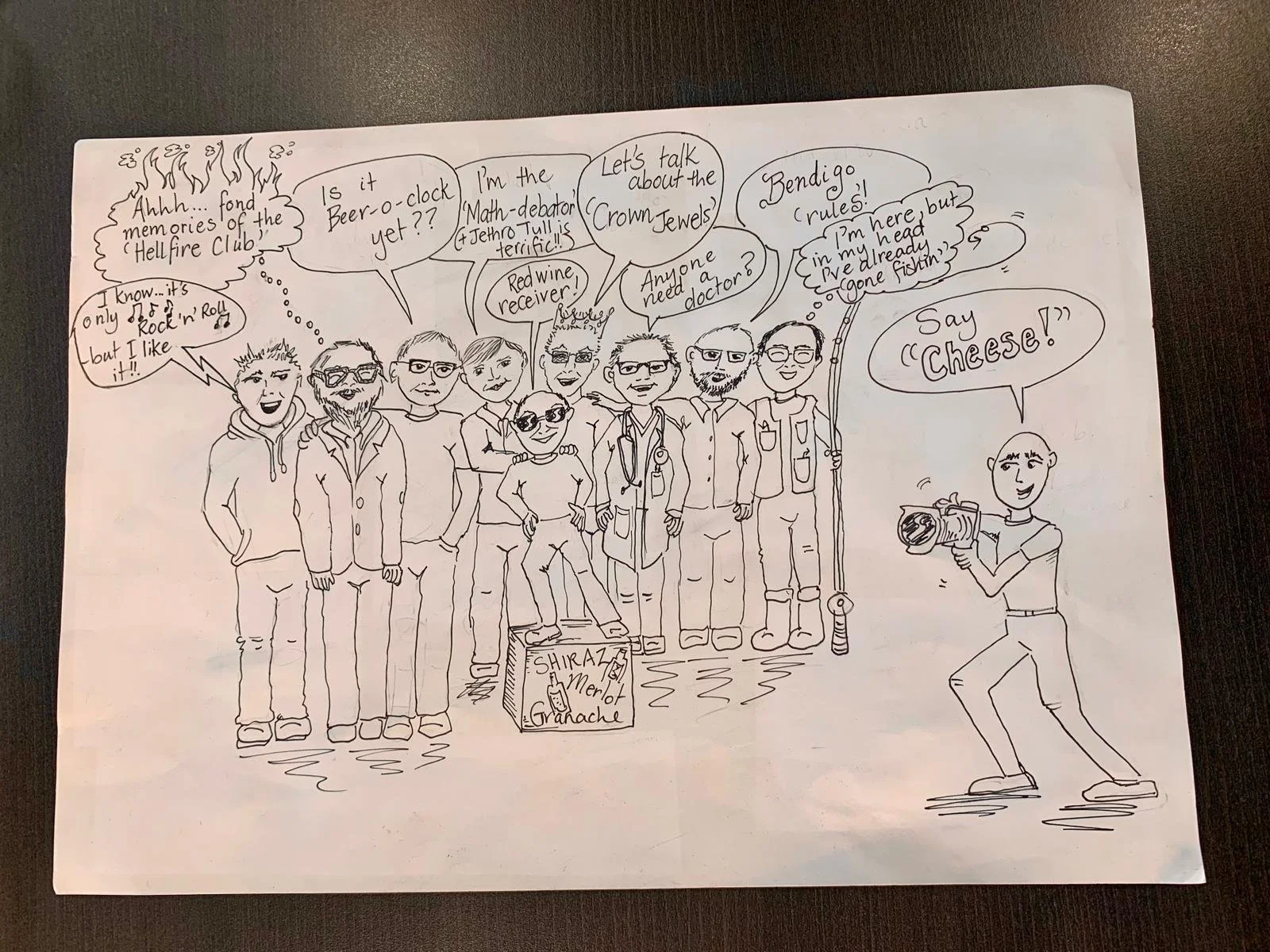

As Molly and the Friday Group members coalesce, their light-hearted banter reverberates through the corridors, along with the bang, clatter and whir of the gym equipment and a consistently well-curated music playlist, ideally without the unpopular Jethro Tull.

Molly Lowther is an exercise physiologist who has been part-time with the Australian Prostate Centre since August 2021. Molly runs the exercise physiology (EP) program and takes several classes during the week. Photographs of past and present EP group members adorn the gym’s door. It’s a gentle, inclusive way to recognise the growing community of class attendees and to honour those who have passed away.

Geoff Elder was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2011. The builder/renovator, one-time geologist and second longest serving member of the group, subsequently underwent a radical prostatectomy after which his prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels hovered around <0.01 for almost 2 years before rising slightly. This indicated metastasis and Geoff had 35 radiotherapy sessions in response, which kept his PSA levels near or at detection limits until 2021. He then started the hormone therapy (ADT) that has kept it at <0.01 so far.

The return of prostate cancer is known as a “biochemical recurrence” and happens to between 28% and 33% of men after initial treatments like radical prostatectomies.

Dan Rabinovici was diagnosed with prostate cancer in June 2019 and consequently had a radical prostatectomy in October 2019. He experienced incontinence for 9 months after his surgery. “I struggle with putting on weight,” Dan says, which he attributes to low testosterone levels. Keeping the weight off is one of the reasons he comes to the class.

Tony Carr was diagnosed with prostate cancer at the age of 76 in 2016. Tony was tested yearly by his urologist and then, in 2016, after reviewing his PSA level and conducting an examination, the urologist ordered a biopsy which led to a radical prostatectomy. It is more common for prostate cancer to be revealed (by testing) at an earlier age. Given Tony’s age, and the challenging treatment side effects, his chosen treatment program focuses more on quality of life.

“I’ve started to realise in the last year or two that it’s important to do the things that are necessary for my quality of life, as opposed to living until I’m 100. I need to support my future quality of life with good fitness regimes. The problem being if I have hormone replacement therapy, I’ve determined that my fitness is going to be affected, my body is going to be affected, to my detriment.”

Martin “Marty” Gregory was 63, relatively fit, running 15 to 20 km per week and looking forward to retirement. He knew something was wrong; the need for him to urinate was increasing at a rate that was not right. From the GP to the urologist, his PSA (prostate-specific antigen) level was 35, and indicated that he had prostate cancer.

“I felt as though I had been hit by a locomotive. Putting it mildly, I was shattered.”

@ Australian Prostate Centre

Peter Baker (foreground, left) was diagnosed with Stage III prostate cancer in May 2023 and consequently had a radical prostatectomy. Peter is a relative newcomer to the Friday Group. He is a retired engineer who helped build large-scale oil rigs in Australian and internationally. He is also a keen fisherman who takes his boat out once a week, less so in winter.

After warm up, group members work through their exercise programs with varying degrees of intensity

Each program is individually designed to alleviate or avoid the side effects of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and hormone therapy (ADT). Side effects can include urinary and bowel incontinence, erectile dysfunction, weight gain, loss of bone density and a loss of muscle mass.

“Resistance training can mitigate the side effects of prostate cancer treatment, including loss of muscle mass, bone density and increased fat mass,” says Molly.

Weight loss can also help improve erectile function.

For incontinence, Molly says, “Personalised pelvic floor exercises, directed by a pelvic floor physiotherapist at key points pre- and post-surgery, can address issues with incontinence.”

These exercises are subsequently integrated into exercise physiology programs.

At times, the men seem to enter a zen-like state, when they are entirely focused on the biomechanics of a specific rep, to the exclusion of everything else, to the beat of the exercise mantra:

Just one breath. Then another.

Just one rep. Then another.

Just one set. Then another.

Just one class. Then another.

It’s almost as if there is an exchange of weight with each repetition. The exertion of lifting physical weight has a corresponding liberation of some of the emotional weight they bear relentlessly.

The kind of strength and resilience to do this kind of weight management can only be revered.

Exercise Physiology Class – Resilience

@ Australian Prostate Centre

Ray wears a “Made Strong” t-shirt in support of his daughter who is living with multiple sclerosis,

Behind him is a picture of legendary VFL player (Footscray Football Club), Edward “Teddy” Whitten.

The not-for-profit E J Whitten Foundation for prostate cancer was established in 1995, in Teddy’s honour, and subsequently became RULE Prostate Cancer (which operates the Australian Prostate Centre).

Some days have nothing to do with prostate cancer and everything to do with a bunch of blokes getting together to do some exercise.

Other days, people share their struggles and fears with each other. They talk about what treatments they’ve had and how they are being affected by them. They talk of what they’ve lost as a result.

Occasionally, inevitably, they receive the news that a member of one of the classes has passed away. The news is doubly poignant. As they mourn the loss of their brother, their thoughts drift to their own mortality and longevity.

Grief is always present, overtly or discreetly. Grief stemming from their diagnosis and the litany of side effects from its treatments. Grief for the possibility they may never be cured.

Grief for what mutinous cells in their bodies have wrought.

“Living with prostate cancer means living with incontinence, loss of strength, fatigue, brain fog and a host of other physical issues. If the physical issues were the only issues, then I think I could deal with it.

But the most significant problem is the deterioration of the relationship with my wife. The intimacy is not there, we are now best friends.

Support is not an issue, and we still love each other, there is no doubt about that. But I now understand why, after a cancer diagnosis, some couples break up.”

“Through the fish-eyed lens of tear-stained eyes

I can barely define the shape

Of this moment in time

And far from flying high in clear blue skies

I’m spiraling down to the hole

In the ground where I hide”

“And then we went back to see the GP.

“Your PSA is actually quite high,” he said. We had no inkling what that meant at all. He referred us to the urologist at the APC, Professor Tony Costello AM.

During that appointment, the Professor sat back and stated, “There’s a lot of cancer there.”

“Oh, God,” I thought. I looked at Michael. I looked at his face. We were both in shock.

It’s all such a blur.”

“My Dad used to say about any problem, “OK, what are we going do about it. How do we fix it and make go away?”

OK. It’s a problem. What’s happened has happened. Now, what’s the solution? What do we do to fix it?

Dad used to say that all the time, and I just feel like I’ve carried that through.”

Yvette Griffin supported her husband Michael after his diagnosis while simultaneously navigating the impacts and fears she also felt, for Michael. herself and their future.

“We have no sexual relationship and intimacy is really hard too, because that was always part of our relationship. So that is a big loss and I feel like we’re just like besties. We’re super best friends.”

“For the first five years after I had my prostatectomy, from the age of 76 to 81, I thought that I was cured and now I know that I’m not cured.”

“To me, the most challenging aspect of living with prostate cancer is the regular PSA tests, to see if the hormone therapy is still working. Lack of energy is a problem sometimes but, as I am retired, this is not so much a problem as it is for those that are working.”

“I did feel different after the prostatectomy. Less of a man. Also, some of my family and my partner didn’t understand how I felt. They made remarks that I sometimes took too seriously then, about things like how it was going down there (as though I should be all good again in the sex department).

I concealed my feelings post-prostate cancer, and I was emotionally fragile. I compensated by throwing myself into work and completing the house renovation.”

“I miss sex.”

“I find it challenging but I haven’t had an erection, really, since July 2022. And no orgasm.”

“I don’t like hormone therapy because you get hot flushes, which are awful, and I’m putting on weight. Hormone therapy also reduces your penis and testicle size. It disappears. That’s another shock to deal with. I recommend people take photos of their penis before they have surgery to remember what it was like because it will be different after surgery and hormone therapy.”

Rob Rowland has been attending the exercise group since 2015. He was diagnosed with aggressive Stage IV metastatic prostate cancer in the middle of 2008. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was elevated a year before, but his doctor advised him to wait a year before retesting. In hindsight, Rob believes that wasn’t a “smart thing to do.” His treatment included a radical prostatectomy, hormone therapy (ADT) and radiotherapy. Having survived that, he has had to step away from the group for several months to deal with life threatening oesophageal cancer requiring surgery and chemotherapy, shown here.

“All of a sudden, your masculinity gets taken away. At the time you just want to get rid of the tumour and throw it away. All of a sudden, you wake up and you’re a different person. You can’t be intimate anymore and that’s a real problem. Most of the guys will tell you the same.”

“Before the cancer diagnosis, I did not think much about death and dying. This is no longer the case.”

Jessica Dickson is the other part-time exercise physiologist at the Australian Prostate Centre. She takes several classes and also subs in for the Friday Group when Molly is away.

“They’ve had a cancer diagnosis, and it can be such a difficult time for people, and this is something that they can then take control of and improve their health when a lot of their autonomy around a cancer diagnosis isn’t quite there. When you get a cancer diagnosis, you listen to your doctor and you do what they say to do. Whereas this is something they can take control of themselves and improve their health.”

“When someone’s passed, I don’t want to tell the group that someone who’s suffering from the same disease has passed away, because it reminds everyone of their own mortality. That’s the bit I really hate. But I always make sure I go to the group who the person was in and I tell them in person first. I also have the fear that people will be forgotten. Which eventually will happen, I know. But I don’t want anyone to feel like they didn’t matter, or they weren’t a huge part of the groups. Because everyone is.”

“We are snowmen

We disappear

Our hearts are nuclear

With hope and fear”

Exercise Physiology Class – Grief

@ Australian Prostate Centre

If there is one place in the world where they can feel safe to be vulnerable enough to talk about their concerns and griefs, it is here in this class.

Like all stereotypes, the one that men don’t talk is tenuous.

“Women are quite happy, as a generalisation, to talk straight away, and men might not,” says Max Rutherford, a psychologist at the Australian Prostate Centre.

“But once men get to that point where they do want to talk or find a situation like this group where they can talk, they do. Then everyone's just talking the same.”

The Friday Group talks. Each member talks as much and openly as they need. There is no pressure for them to say anything more or less then they want.

Talking also means listening; feeling heard is a mighty weapon against isolation and its friend, despair.

Talking, listening and feeling comfortable enough to feel collectively engenders the connectedness that facilitated by the exercise physiologists, Molly and Jess.

Molly keeps an eye on things by spending time with each of member of the group to see how they are travelling. If they ask, she can also give them advice or suggestions. On the days that Molly can’t make the Friday morning class, her colleague, Jessica “Jess” Dickson, takes the reins with the same care. They are both integral to the group and their efforts are deeply appreciated and respected by the men.

The class, the gym and the exercise physiologists create one type of experience that, almost surreptitiously, creates another. A place and moment in space and time with cloth, needle and thread that the men use to weave together a comprehensive support system.

This is the multifaceted ethos of exercise physiology – quality of life through improved physical health and, in turn, improved mental health.

“Support work is part of it and, with the mental health, is to create that safe space where all these things are normalised. I never push them but, when they get comfortable enough with me to talk about sexual function, psychology, incontinence, anything like that, it makes me think, “OK, this person’s comfortable. They trust me.””

“I feel the connection with a lot of people. I’ve always been quite an empathetic person. I think of people going through these journeys and they need as much support as possible. I don’t want anyone to feel like they’ve been neglected or falling through the gaps or left alone.”

“It’s probably more about mental through physical; we encourage the movement, but we facilitate the group setting and that group support for the mental health side. Movement should be about quality of life, not necessarily getting stronger and fitter and better. That’s a nice effect, I think, predominantly in the cancer survivorship phase.”

“I find the big part of it is mental health. We all know we should exercise, but why do people not exercise? Because it’s hard to have motivation and show up week-on-week or every day. There are other things that keep the guys coming back that aren’t just about the exercise. If that was the case, then we wouldn’t have them all talking and bantering in the groups.”

Mark Harrison, Australian Prostate Centre CEO, meets with the Friday Group to address their concerns about the progress of the much-needed gym extension. The gym is not able to scale up to support increasing class sizes. The investment of the group in the gym means some hard questions for Mark, but also indicates, in a way, a successful outcome for the group – their support for each other is important, which could only come about because the exercise physiology classes happen.

“I was pleased that they wanted to raise it because they take a bit of pride in it. I was pleased they did it and I empathised with their frustrations. I’ve had a perpetual frustration of trying to expand that gym. It comes down to a whole balancing act between funding and, because we don’t have a large corpus, we’ve got to get the money before we can spend it to do the building works.”

Molly’s dog, Dexter, makes an occasional visit to the Friday Group sessions. Dexter only wants one thing - attention. He gets it in spades, but gives a lot more to the men than he realises.

“The most important benefits of the exercise physiology group are the camaraderie and trying to improve my fitness. The APC [Australian Prostate Centre] staff are terrific, very skilled and great communicators.”

Exercise Physiology Class – Support I

@ Australian Prostate Centre

The Friday Group’s support system extends beyond the confines of the gym.

They have a wide-ranging Whatsapp chat where they discuss anything and everything. One of the loveliest aspects of the chat is that holidaying group members share photos and stories from their adventures, and then they all chat about it, staying connected despite the distance.

The Friday Group also organises and attends social events like quiz nights, dinners and fund raisers for the Australian Prostate Centre.

They have established an entire social life with the same qualities as the class. Perhaps the most fundamental of all the qualities is the group’s level of care when one of its members is not doing well.

Rob Rowland is currently longest serving participant of the Friday morning exercise physiology class, but had to miss it for several months after being diagnosed with aggressive oesophageal cancer.

Already compromised by living with prostate cancer, there were serious concerns about his chances of surviving the long and complex surgery. He then had to undergo chemotherapy that lasted a couple of months.

It made no difference that the cancer wasn’t prostate cancer. All that mattered was one of Friday Group needed support. And he got it for the duration of treatment and recovery. He continues to get it. Everyone continues to get as much as they need.

The group visits Rob for lunch at his home in January 2024, a few days before his risky and complex oesophageal cancer surgery. Rob’s chances of survival are not high. On Rob’s left is his son-in-law, Stuart David.

Rob’s daughter Michelle David (right) has been a key support for Rob throughout his journey, embracing the fact that Rob had prostate cancer, rather than hide from it. Michelle has been as active in involving her children in Rob’s journey, including Emily-Rose (left). How deeply Rob appreciates the support is immeasurable.

“For Dad, it’s about surrounding him with people and family who are going to lift him higher. He has the most beautiful relationship with us and his grandchildren; he adores them and they him. It’s about the good times, the fun, smiles, laughter, and the memories, but also being there when things don’t fall the right way.

When someone has cancer, the whole family and everyone who loves them goes through it too.”

Rob with his grandson, Lachlan.

Lachlan and Emily-Rose made the teddy bear, Dash, for Rob to take with him on his prostate cancer journey. Dash has had a significant influence on that journey. His presence in hospital visits gives his doctors, nurses, visitors and other patients a kind of social entry point to start a conversation around. Dash has at least 2 passports filled with comments of support and love from all of them, making the experience a little brighter for Rob.

Marty and Michael visit Rob in hospital during one of his chemotherapy treatments for oesophageal cancer. They spend an hour chatting about how Rob is going, what’s been happening with the Friday Group and tell stories. They make a pact to share a bottle of red when Rob has completed his treatment.

“There are times when appointments and hospital stays put a huge strain on family and friends. It is a simple thing to offer a ride or make a visit, but a great help to those in need. I would do anything for those Friday blokes, I love them. Well, almost anything.”

“Without having those type of people around you, honestly, you are on your own and you believe you’re on your own and you think you’re the only one on the planet that’s been affected by it. In your own mind, you’re self-destructing.”

“Rob and I hit it off. We like each other’s company. We really only became close over the last two years, although we’ve known each other for a bit longer. My biggest thing with Rob is he got diagnosed at the same age as me, he has the same cancer as me, he had the same scores as me. Everything about him was the same as me. I look at him as my yardstick of where I’m going to be next.”

Exercise Physiology Class – Support II

@ Australian Prostate Centre

Supporting the self is as important as support for each other.

As Max Rutherford, psychologist with the Australian Prostate Centre, says, “People tend to do better if they have some sort of directional focus for their lives, which could be as simple as wanting to look after their children or their grandchildren, or having a love of gardening.”

For Michael, that is making and drinking beer. Home brewing is his passion. It seems like he has a new t-shirt for some brewery every gym session.

There is certainly something therapeutic about the process. The technical aspects of the ingredients, measurements, temperatures, time frames and alcohol percentages, as well as the physical craft of working with the ingredients and equipment, then the smell, the colour, the pour and, of course, the taste. All around the redolent smell of hops.

It’s a process he shares with the group, too. He will regularly have group members around for tasting, and has organised a fundraiser around it that netted almost $8,000 to go towards exercise physiology gym extensions. Other fundraisers have been held at bars making craft beers by people Michael knows.

For Yvette, his wife and supporter, there is the garden, a therapeutic place for her to manage her own physical and mental health as someone living with and caring for a person with an aggressive prostate cancer.

There is spending time together as well. The intimacy they once had has now gone but has evolved in different ways by sharing time with each other doing the things they love.

“I went on the wagon, did the operation [radical prostatectomy], did everything, and then went back to meet with the professor [Professor Tony Costello AM, urologist]. And I said, “I’m not drinking at the moment.”

He wrote out a script for one bottle of red and gave it to me. He said, “Enjoy yourself”.

That’s basically what I’ve done ever since.”

“I really feel connected to my Dad in the garden because he always gardened. Mum loved the garden too, but Dad was the one always out there doing the work.”

“I don’t know how any guy can do it on his own. You need to have someone that can support you. I’m really lucky because Yvette is very considerate, loving and patient.”

Exercise Physiology Class – Support III

@ Home

The Friday Group has an energy about it. You can hear it from outside the gym. You can see it as you step through the doorway. You can feel it once you are inside.

At some moment, someone will say something and the banter kicks off and stays on until they leave.

Everything is discussed; politics, sports, the arts, world news, treatments, side effects, advice.

The Collingwood AFL team makes a regular appearance in conversation, from the highs of the 2023 premiership win to a more challenging 2024 season.

Just as footy teams need to reshape themselves at the end of every season, men with prostate cancer need to reshape their lives. The Friday Group includes men from their 50s to their 80s. Which means they have had to adapt the latter stages of their lives to a new shape that could be diametrically opposite to what they were building towards before diagnosis. This type of pivot can be sudden and very challenging later in life.

But, their age means they have lived a fair chunk of life, and hearing them relate their rich, diverse and almost endless collection of stories is wonderful.

They have worked across many disciplines. They have travelled to and lived in many places in Australia and around the world. They have met and formed relationships with many people. It would take lifetimes to share their collective stories. But they have go.

Fishing. Building oil rigs. Living in Belfast during “the Troubles”. Sitting in a hot spring in Iceland warmed by a volcano that was about to erupt. Being a sports trainer. Being a teacher. Collingwood’s 2023 premiership win. Nipple piercings.

As lovely as it is to hear the stories from their past, it’s even more so to hear the stories they are still collecting. From the experiences they are still having. From the lives they are still living.

“They love me asking advice and I’m sure Jess as well. I get all my political news and current affairs, everything, from these guys.”

“Dan comes up with some wise cracks every so often, and sometimes he’s just hilarious because he comes out with some leftfield stuff.”

“It’s just sharing stories. It’s just sharing time together. It’s just sharing conversations. It’s not always about cancer. Sometimes, I don’t want to think about cancer or talk about cancer.”

“The most important benefit of the exercise physiology group to me is the social interaction. It lifts my mood, and I form new friendships, even late in life. It also encourages physical activity, which is important to longevity.”

“Marty and I, for some reason we just clicked. I think if we had been brothers, we probably would have been ridiculously close but may have also fought the whole time. He’s just a really good guy.”

“They offer me more hope and motivation. They are mostly a really positive bunch of guys going through something that I hope I or my close loved ones never go through. At the same time, it gives me hope, that it’s not the end of the world if it does happen because these guys are still doing pretty much everything they want to. Some of the side effects suck, but they all found each other and bonded over it. They’ve created this community that will go on far beyond my stay here.”

Rob is finally able to do exercise physiology again in June 2024, after several months away to treat oesophageal cancer, which he has survived.

“Sometimes we go in there and we just muck around. Honestly, we have fun, we muck around. But you walk out of there so much happier.”

“I came home the other day and I was nearly in tears telling my wife about it. How humbling it was and how everybody gathered around me to see me and so excited to talk to me again.”

Exercise Physiology Class – Camaraderie

@ Australian Prostate Centre

In a few moments, the chaos and energy of the gym session eases to a gentle hum. Everyone gathers at the end of class to sit and warm-down.

The release of tension is palpable. Whatever drugs the brain produces through exercise are released.

Then it’s done.

The playlist stops.

The men grab their gear. Some linger to finish their conversations, follow up with Molly or Jess, or discuss any social plans the group might have.

Some of them head off for work or home.

A few head down to St Cooper café for a(nother) coffee. Or two.

Exercise Physiology Class – Warm Down

@ Australian Prostate Centre

Back at St Cooper café for another chinwag.

It’s as if the world is fully aware of prostate cancer and they can talk about any aspect of it they like.

This is not the reality of the world they inhabit.

Awareness is the one thing everyone hopes for more of in the broader community. Enough that everyone in the Friday Group could have the same type of conversations about prostate cancer and its impacts anywhere, with anyone, without stigma and fear. The more people talk, the more people know. The more they know, the sooner they get tested. The sooner they get tested, the greater their chances of survival. The more they can talk about it, the greater the impact to their survival and their quality of life.

We are not there yet but the group can at least have that in the smaller part of the world they have made for themselves, held together by the bonds of their shared experience and camaraderie.

And, perhaps, faith; At times, prostate cancer seems like both illness and spirituality for the men and the people that support them.

The tenets of exercise physiology are the basis of their scripture, the group their congregation, the exercise physiologists their pastors, the class their mass, the Australian Prostate Centre’s gym their chapel.

And then, in the warmth of the café, with Tabita and Stephen look after these weary pilgrims. The men sit under hanging lights that shine like stars, reminding us of those with prostate cancer whose journeys have ended. The café’s logo has an almost angel-like wing in it.

For many reasons, it’s not hard to imagine St Cooper as the patron saint of men living with prostate cancer.

Steven Cooper, co-owner of St Cooper café (with partner Tabita Cooper), listens to the men as they talk, because he cares and because it helps him gain some understanding about his father’s journey with cancer. “I do try to listen now to see what they're saying, you know, as if it ,was a way of getting insight into what my dad is going through,” Stephen says.

“There was one guy that was coming in. He was a bit grumpy and not very talkative. But since he’s been coming with this group for a while, he sort of slowly opened up, and we were almost taken aback; he was asking how we are a couple of couple of weeks ago! So, I presume the group has been of help to him and makes him feel like he’s not alone.”

Coffee – 7am

@ St Cooper Café

ॐ

Glory to the shining remover of darkness

CODA

“I focus on the importance of family and friendships and don’t let that focus slip.”

“When I was working in a building team years ago, I did feel that I couldn’t talk about it to some people - blokey types who had no empathy.

I asked one guy, maybe 10 years ago, “How are you going?”

”OK,” he replied. “Better than you.”

It hurt.”

“Since meeting the fellows in the Australian Prostate Centre, and through WhatsApp, I have found that I can talk about prostate cancer matters more freely.

With the camaraderie and mutual support, and even though our ages and backgrounds range widely, this group has become a great coping strategy.”

“When I saw the oncologist [after the prostatectomy], I asked, “Have I been cleared cancer?”

“No, John,” he said.

”You’re living with cancer.””

“I tried to get onto a psychologist, which eventually happened.

“Why do you want to see me?” he asked.

“Because I’m scared of dying. I don’t want to die,” I said.”

“All the research indicates the importance of exercise and getting out to walk or run.

There is another side which is much harder: mental wellbeing. Pre-cancer, I considered the need for mental wellbeing as a weakness; I now know how wrong I was.

Without Molly and Jess, the others from APC, and especially the blokes of the Friday group, I would/could not cope.

I feel we are a band of brothers. We all come from different walks of life, but we are on the same path and together we will make it.”

“I had a lot of problems talking about it and that’s why the Friday Group is so important to me, because everyone there has the same sort [of prostate cancer]. They have different journeys, but the cornerstone is the same. We all talk about what we’re going through and we open up to each other.”

“I got two very low PSAs [prostate-specific antigen test results] at the time, and I thought, “OK, we’re winning this.” I asked Ben [medical oncologist], “Am I in remission?” He just looked at me and shook his head. He said, “You’re never in remission.” I thought remission was something that does happen. But, he said, “No, not for you, not for guys that have metastatic test results.””

“It’s the sort of thing I know sounds ridiculous, but there’s not a day that I don’t think about the disease and when I am going to lose the battle.”

“You come to think that you understand why people leave their partners. When someone got sick, got cancer, and they split up, I used to think, “Oh, my God, that’s terrible when they’re so sick. To desert them.” But, in fleeting moments, you understand why that might happen as coping can be very hard.”

“Early detection and treatment is the key as several organisations have stated. I read an article by Chris Tuohey in the House of Wellness magazine from Chemist Warehouse. He encourages men to choose testing over ignorance.

He stated “early detection is key to not just surviving but thriving post-diagnosis. Life after cancer can be full, fit and fulfilling.””

“The exercise program is essential to combat the side effects of the treatment, including loss of strength and bone density. It is also great working out with the others in the group as this provides great support.”

“And the most important part is living. You’re trying to survive day, day after day, year after year. And you don’t want to give that up either.”

“A lot of it is your mental state that you’re dealing with. That’s as important as anything else. The positive attitudes, the support you get from the guys that are in the same situation as you are, all different stages, different places. The support is unbelievable. And it’s fun!”

“Halfway through the time that I’ve been with the group, I realised that I was motivated to get up at 5:00 or 5:30 in the morning and be on my way. And I was truly motivated, you know. I welcomed the opportunity to go. Partly because of that camaraderie, that there were people there that wanted to have a coffee with you before the gym and have a coffee with you after the gym.”

“And I’m of the view that if I can have quality time in my life now that’s going to be really important. I’m thinking more along the lines of living with it or dying with it rather than from it, if I can get to that point.”

“The earlier people are tested, the better the treatment and the better the chances they have of not getting a terrible prognosis.

The more awareness there is, the greater the funding that goes into exercise or treatment in general. Then, more people are aware that this is something they could be doing.

So many people we get come in and say they’ve had prostate cancer for X amount of years and this is the first time they’ve heard about the Australian Prostate Centre, and they always wish they knew about it earlier.”

“I couldn’t imagine working anywhere else at the moment, but I do think there’s a limit in this particular space because of the emotional requirements of the job. Yeah. Maybe there might become a turning point when they’re all new people in the group, there’s new staff, and I’m not bonding quite as much, or I’m just fatigued.”

“They offer me more hope and motivation. They are mostly a really positive bunch of guys going through something that I hope I or my close loved ones never go through. At the same time, it gives me hope, that it’s not the end of the world if it does happen because these guys are still doing pretty much everything they want to. Some of the side effects suck, but they all found each other and bonded over it. They’ve created this community that will go on far beyond my stay here.”

“In terms of funding, there are the broad funding pools from government, coming from funded agencies and the Health departments (state and federal). Then you’ve got the National Health Medical Research Council that’ll put out certain amounts of money for cancer. It’s a very competitive market and prostate cancer, it would be fair to say, is slightly under-represented in terms of its funding compared to its prevalence in society.

I think it sometimes struggles a bit with the public perception that every person with a prostate will die with prostate cancer. I think some of the other cancers have done a much better job at profiling and are more structured and aligned in trying to find those funding pools.”

Acknowledgements

This story does not exist without John Hall, who so readily shared with me his experiences with prostate cancer. He often talked of the wonderful group of men he did an exercise physiology class with and I felt like I needed to see what he was talking about.

It literally took about 5 minutes of being with the men of the Friday Group before I felt I couldn’t not do a photographic story about them. About the love. Dan Rabinovici, Geoff Elder, Martin “Marty” Gregory, Michael Griffin, Peter Baker, Ray Barber, Rob Rowland and Tony Carr are fantastic, diverse and lovely group of blokes who shared such personal details about their experiences with prostate cancer. In the worst of times, the best of humanity shines through. When people stop caring about how they differ and coalesce around how they are common. We all feel love, pain, loss, grief, joy. We all want to feel heard and understood. This is the foundation of the Friday Group and I cherished the opportunity to be allowed to experience it. Thank you, so much.

Molly Lowther and Jessica Dickson are such beautiful people who genuinely care about the men. Sometimes the exercise physiology aspect of the group seemed nominal but never the most important reason they were there: to help improve quality of life. I’m not sure they will ever truly know how deeply the men of the Friday group feel about Molly and Jess and how much the men appreciate what Molly and Jess do for them.

As CEO of the not-for-profit Australian Prostate Centre (and RULE), Mark Harrison has a hell of a job trying to keep the ship afloat. But it’s a majestic ship with an incredibly important purpose, and run by a fantastic crew. There is a much longer photographic essay that is needed to relate their part of the story that makes the Friday Group possible. For example, Dr Jane Crowe and psychologist Max Rutherford shared their time and experiences which are worthy of being told and heard. They deserve it and more, for what they do and create.

This story is truly about the men and the Australian Prostate Centre but St Cooper café shares in the story. It is the place where many of the Friday Group start and finish their exercise physiology classes. It is a rare place in the world where the men feel comfortable to talk about prostate cancer in public, without fear. It is what the Australian Prostate Centre and the Friday Group would like to see the whole world like. The café absolutely expresses who Tabitha and Stephen Cooper are.

I wish I was a great photographer with many people who cared that I made photographs. As many people would then see this story. Then maybe the needle of prostate cancer awareness would shift a little and men with prostate cancer would have correspondingly easier and better lives. I am not a great photographer but I went about this story like any other and gave it as much as I could. I hope, at least, that you all feel heard.

Photographer’s Note

This is the last photographic essay I will do.

It is too long, with too many loose threads. Yet, it is the story I am publishing. It seemed wrong to cherry pick the “best” photographs. I felt very uncomfortable with the idea of showing, say, one man feeling pain while another feels joy. This is the conceit of photography - that a single photograph tells a story. It does not. Humans are not that simple. Each of these men feel all of the feelings. Strength. Grief. Support. Camaraderie. Frustration. Pain. Humour. As such, I’ve included photographs of each of the men in each of the sections. The result is much longer than “real” photographers would think appropriate. If I was a hard-ass, I’d think the same. But I think it’s good the way it is.

I think Leonard McCombe would have thought it was too long and I’d probably be swayed by him. I have travelled far with photography and, during that journey, McCombe is the only photographer I’ve found who understands the practice of documentary photography the way I do. Hence the quote at the start.

Photographers don’t know shit about who they are photographing or what is important about them, at the start. To learn even a fragment, a photographer must spend time with the people they are photographing. They must open themselves up to those people and what they are experiencing, as much as they can. Well … that’s the only way I could approach it.

But empathy is not a gift, it’s an exchange of energy. Being a documentary photography has always been about giving as much empathy as I could. To the point I have had one mental breakdown and several mental health episodes. The end of each story feels like the worst breakup I’ve had. Who subjects themselves to that, repeatedly? I did. But I can do that no more.

I need to replenish 15 years’ of my spirit.

I am proud that this story is where I stop.